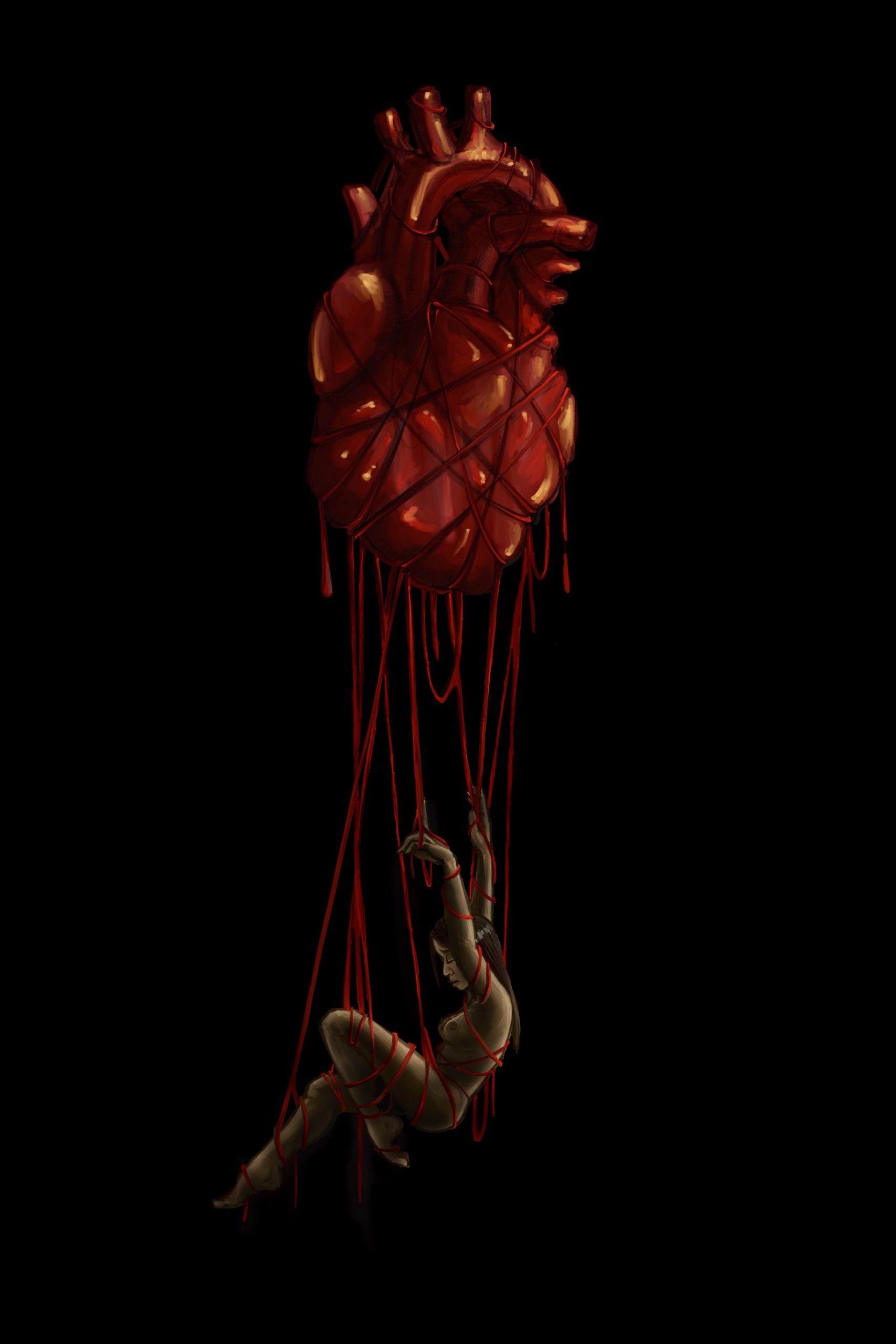

I painted this piece entitled, “Tethered Heart”, over Christmas break. It’s not exactly what you’d expect on a Christmas card, but the holidays can be tough for some, myself included. My painting, symbolizes the struggle of feeling bound by complex emotions, grief, and past traumas. These feelings can sometimes hang on my heart, tugging at it, and constricting it, entangling me in a web.

Anyone who has lost loved ones or who are estranged from their families may be particularly prone to melancholy, depression, or other mental health issues during the holidays. One of the worst aspects of developing these feelings during this time of year, is that it feels even more difficult to express your feelings. No one wants to be the person who is a major downer during a holiday that’s supposed to be all about joy and merriment. This is a common feeling especially for trauma victims.

Often, trauma victims have deep worry and anxiety around being a burden to those around them, those they love. The irony about this is that their loved ones are the people most invested in wanting to help them – but they can’t if they don’t know about your needs. Still, I know first hand how hard it can be to break that silence in honor of your needs and self-care, in honor of your self.

When I was painting this piece, I was in a place where I felt stuck or trapped in a few different ways. A part of me wanted to partake in the joy of the holiday, be with my family. Another part of me clearly recognizes the degree of trauma I experienced growing up with my family. I don’t entirely blame them for this, much of it stemmed from generational trauma, but it still makes being in their company, fraught with mixed feelings. It ties my heart up in knots.

Even more painfully, is the fact that my brother passed away in the winter-time and one of his favorite holiday’s was Thanksgiving. Nor was I able to give him is last Christmas gift, before he died unexpectedly. So, as much as I want to smile and find the joy in life, it can be hard to untangle myself from this complex web of feelings.

Body Memories

This winter I started to feel like a fly caught in a spider’s web. I struggled and fought it at first. But you can only struggle for so long without help. Eventually, a dull hopelessness crept into my heart. Some may know this feeling by its other name: depression. In the cold of depression, I felt naked and unprotected.

TW: I talk about a domestic violence altercation in the next paragraph.

When I was around 14, I experienced a moment where I thought my life was in danger. Terrified, I fought back. I defended myself as my thoughts were racing. When I felt my strength was failing me, I said to myself, if you continue fighting it might only make things worse, so I froze or went into collapse.

This is the exact behavior a prey animal, like an impala, might exhibit upon being caught by a predator, like a cheetah. On instinct, when in danger, an animal brain will frantically search for solutions in an attempt to keep the body safe and alive (fight, flight, or freeze). Humans also have this instinct.

Can I fight my way out? Can I run away? What if I freeze up so they think I’m already dead? Will they still hurt me? What if I just submit to it, will it be over faster and with less suffering?

The part of your brain that is largely responsible for this focused, high adrenaline, state, is the amygdala. The amygdala will basically turn off the other parts of your brain so that you can devote all of your energy to the present danger. This means shutting off the prefrontal cortex which is the part of your brain responsible for much of your memory. This is also why, after a life-threatening event, trauma victims may struggle to retell a cohesive and clear story or why they may have no memory at all.

Another example is the opossum that is surprised and immediately plays dead. That’s a freeze response or in other words, the brain trying to keep the body safe. Just like the impala or the opossum, I too froze under the weight of threat.

If an animal is still unable to get away from a predator, their brain will continue its response to threat by shutting down sensation as well. At this point, the brain still hopes that as soon as the danger passes, there may be an opportunity to run away to safety. How well can you run away if you’re in searing pain?

Let’s return to my feelings around the holiday season. If you think about the symptoms of depression, they are numbness, low-energy, lethargy, crying spells, hopelessness, isolation/withdrawing, etc. And many people find themselves just “going through the motions” without much interest in daily living or connection to things they once loved. This is sometimes called “functional freeze“. Depression is a form of functional freeze.

I am a curious person, even when I’m depressed. So when these feelings hit during the holidays, I thought to myself, where was this coming from? For some folks, they may stop at saying, “well, I lost some of my loved ones and my family is…complicated”, but that’s how my brain interprets reality. I wanted to know, what my body was experiencing. Why was it reacting this way?

This traumatic event happened over decades ago, but in reflection I started to notice something. My reactions in that situation were almost entirely driven by instinct and mirrored almost perfectly how prey animals react to danger in the wild. It was almost as if, my body was the one making the decisions not my my rational brain. My brain had no blueprint for that kind of interaction prior to that event. It was all biology, my friends. My body’s natural instincts kept me safe.

Trauma research is beginning to reveal that the body, or more specifically the nervous system, plays a much more significant role in our mental health than we previously understood. The body can often sense danger even before we are consciously aware of it, almost as if it possesses its own memory separate from our conscious understanding of what danger looks like and can retain that “memory” for the rest of our lives. Unfortunately, sometimes, our bodies react too intensely, too quickly, or too often to perceived threats that aren’t actually there. Understandably, it’s our body’s way of trying to keep us safe, but it can seriously disrupt our mental wellness.

Knowing this, I started to wonder if depression was a kind of reaction to a threat in my life, that I just couldn’t consciously see, but that my body was perceiving. I thought long and hard about this; what was it that was making my body freeze up?

Grief as an Instinct

As humans, we are social creatures. We thrive on connection, our ability to collaborate with one another. It’s how our species has endured and evolved into the dominant species on the planet. It’s not a stretch to say that connection, which is often strengthened through love, is critical to our survival.

It may surprise you to know that, as a social species, one of the things we share with other social species is the concept of grief. It’s a fairly new domain of study for researchers, but animals exhibit specific and measurable behaviors in response to loss often relative to the strength of the bond to the deceased. This has been observed in dolphins, orca, chimps, gorillas, giraffes, elephants, crows, dogs, house cats, and more.

Earlier, I mentioned that almost all animals have a specific threat response that usually goes something like: fight, flight, and freeze. These make logical sense as an evolutionary adaptation to keeping animals alive. But, if social animals also exhibit grief, which can cause these creatures to withdraw, isolate, feel sadness, stop eating, etc. – what possible benefit might grief have from an evolutionary standpoint? Why is that built into the the blueprint for the social animal brain?

When someone dies in our social circle, not only do we have to come to terms with the feeling of that loss, the permanence of it, but our social structure changes. Our relationships must shift in response. Someone who may have provided safety, made you feel secure, is gone. If connection is what keeps us alive as a social species, then what happens when those connections change or are lost?

Perhaps, our brain responds to these changes through the experience of grief. Grief is extremely painful, but pain can also be helpful. Pain can teach us how to respond to keep ourselves safe. If we want to purely look at loss through an evolutionary lens, losing a loved one threatens our safety. It should hurt. We should want to prevent this from happening. Pain is a powerful motivator, but the loss also threatens the stability of our social groups. The closer the deceased was to you, likely the bigger role they played in helping you feel safe (even if it was just psychological safety); therefore, the greater the threat to your survivability, to leaving you vulnerable.

It’s no wonder we may feel lost ourselves during a time of grief. If you have every lost someone close, you know this feeling well.

For humans, this same experience can be felt through the loss of a long-term relationship or a permanent break up with a long term friend. Or perhaps, the realization that your once closest social circle, your immediate family, isn’t actually safe and that you may need to create distance for your own benefit. At it’s core, I think that was my situation.

The holidays are about connecting with loved ones after all. But they are also a reminder of those we have lost, the pain of that loss, and our own vulnerability. Perhaps, I wasn’t just depressed because of the reality that I missed my brother and struggled with connecting to my family. Perhaps, I was depressed because I felt like an impala, separated from the herd, alone and surrounded by tall prairie grass where danger could be lurking anywhere. There isn’t nothing to fight. Running might actually cause something to chase me, standing still, freeze, starts to make a lot of sense.

We retain a lot of our cognitive blueprint from animals even though we often think of ourselves as far removed from the rest of the animal kingdom. Understanding my own behaviors in the context of how animals behave can be helpful.

After a traumatic event, many survivors start to develop a belief that they are broken or damaged. Often this is in response to symptoms like anxiety, depression, shut-down, anger, erratic moods, ptsd, etc. The inability to pinpoint the origination of these reactions, or control them, can be frustrating, and lead to thinking there must be something wrong with us personally. However, if we reframe the symptoms of this ‘brokenness’ as normal reactions to a dangerous event or environment, we start to realize that we’re not broken at all. Our bodies are just trying to keep us safe.

Perhaps a better strategy than blaming ourselves, getting angry, or punishing ourselves for these reactions, is to simply give ourselves grace and understanding for what’s happening in the body, and find ways to help process through it. Guess what?There are actually several therapies that focus on doing just that!

Eye-movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy helps clients sort of uncouple the body’s reactions from those memories. The idea is to let the body know, that we are no longer in danger. The second therapy is called Somatic Experiencing therapy. This therapy is based o the theory that, perhaps we didn’t get to finish out the full life-cycle of a threat response. That is, we got stuck, in freeze (for example) and didn’t get a chance to come down from that feeling, to understand the threat was over. This can lead to a dysregulated nervous system that is out of sync and responds unpredictably to perceived threat. Both of these therapies are based on body memory and you can read more about the research on that by checking out The Body Keeps the Score (Van der Kolk, 2015).

There are also many other talk therapies that can also be helpful for processing traumatic events. However, many trauma victims, especially when it comes to sexual violence, have difficulty re-telling their stories. The advantage of body oriented therapies like EMDR or SE, is that you don’t necessarily have to re-tell your story. Instead, the focus is on helping your body react more appropriately in the here and now. You can also visit the resources page to find more books and resources on healing trauma.

One more thing I haven’t mentioned about grief. The feeling actually shares something with the Christmas holiday. They both remind us of our capacity to love.

Leave a Reply